In the 80s, a seemingly simple innovation changed the course of FMCG sales forever.

A rural entrepreneur noticed that poor consumers couldn’t afford the ‘new necessities’ of the FMCG world (e.g. Hair Oil and Shampoos). These daily consumables came in large pack sizes whose unit-price was too high for those buying their grocery based on daily or weekly consumption.

This insight sparked an innovative idea.

He modified a machine that sealed PVC (plastic) folders. He then took some transparent hose material used to water plants. He sealed it at one end, filled it with water and sealed off the other end. After multiple iterations, he got a small device that held a few ml of water.

Ecstatic, he started selling hair oil and shampoo in such small packets in and around his hometown. Consumers who found larger bottles of these products unaffordable began buying these low-priced units (LPUs) repeatedly, and eventually, big FMCG companies started to sit up and take notice.

Thus began the sachet revolution.

The entrepreneur who pioneered the idea was Chinni Krishnan, an agriculturist whose son C.K Ranganathan ultimately launched the Chik Shampoo in a sachet pack, priced at Rs. 1/-

Sachet, and the low putdown price revolution it kicked off changed the face of FMCG sales. It opened up rural markets to companies who had hitherto struggled to crack them.

The idea of a sachet was a masterstroke- it helped brands overcome a formidable consumer barrier without making any fundamental business changes.

Over the last decade and a half, we have seen many examples where brands have overcome consumer barriers- stimulating trials, repeats and engagement- through clever hacks, instead of fundamentally altering their offering.

Here is a list of our favourite examples:

A lot to “Like”: the innocuous “Like” button that now seems to be a part and parcel of almost every website was actually brought in by Facebook after a lot of debate and consideration. 3 years into its launch, Facebook only had “Comment” and “Share” features that allowed users to express their approval and thereby help Facebook understand the popularity of the post. However, the problem was that these interactions required a deeper engagement and not everyone who went through the posts would show this level of engagement. The “Like” Button was a perfect solution to this dilemma.

However, Mark Zuckerberg had a legitimate concern. He suspected that the “Like” button might become a lazy way to show approval and preclude deeper engagement. A closer look at consumer behaviour proved that these concerns were unfounded because the posts that had higher Likes also got more comments and shares. Clearly then, by allowing an easy way to express approval, the Like button democratized expression and hence encouraged higher participation.

Likes gave Facebook the ability to generate a disproportionately large amount of interest data about a very large number of people, thus powering social media and its advertising business overall.

Today, even as “Likes” have been split into 7 emotions ranging from Love to Anger, the “Like Button” is not just a ubiquitous social media feature, it is also a pop-culture icon for showing approval for anything- in both real and virtual worlds.

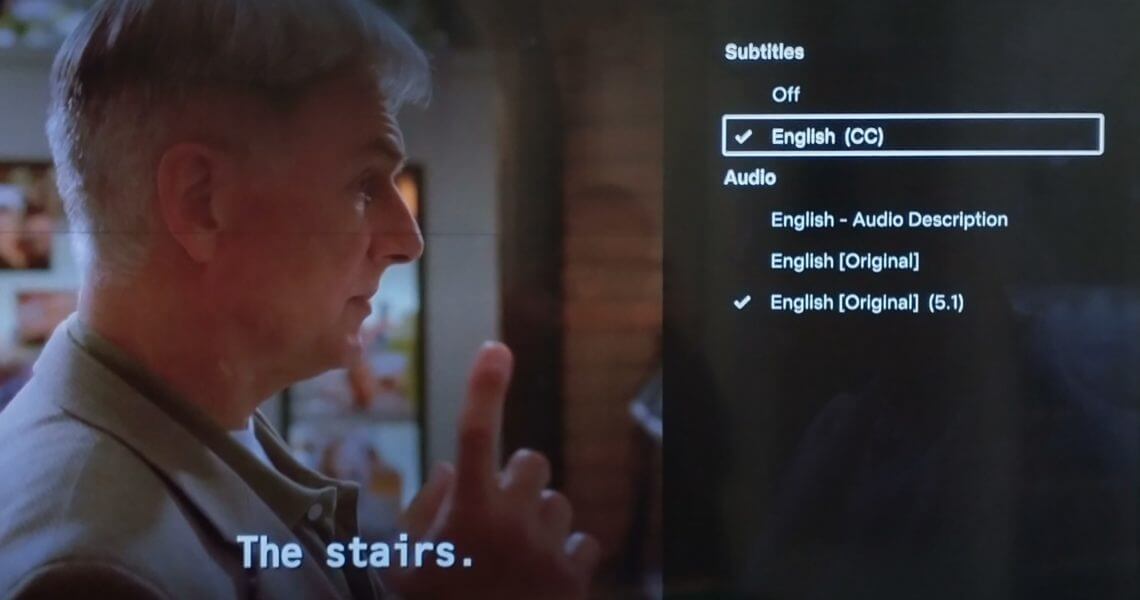

English-Vinglish: Indian viewers have always been intrigued by English content. However, difficulty in following the accent and ‘getting’ the dialogue limited its appeal, even among the well-educated, English-speaking crowd. While dubbing was a workaround, this cohort felt that dubbing compromised the true spirit and essence of the content. They wanted to enjoy English content in its original form but wished there was a better way to ‘follow’ it. This unmet need was limiting the category growth.

Around 2010, English channels like Star Movies and HBO started adding subtitles to their English programs. In 2011, Warner Bros launched a few prints of Sherlock Holmes with English subtitles. Both experienced great results. Over the last decade, English-on-English subtitles have become a deceptively simple solution for broadening the appeal of English content and have become a default option with all English content streamed on OTTs as well as cable. Interestingly, research conducted by IIM-A has proven that English-on-English subtitling (or same language subtitling in general) has also had an unintended positive impact of enhancing language comprehension and speaking skills of viewers!

Now Showing: towards the end of 2000s, Facebook found that even though its users were spending a lot of time browsing through its feed, they skipped past the videos without watching them. In particular, if the video happened to be a promotion or an ad, it was almost never viewed. A bit of research revealed a deeper truth about this behaviour- while consumers could take a quick call on whether to spend time on textual updates based on its introduction and title, the lack of an easy preview limited the opening rate for videos.

In September 2013, it launched ‘Autoplay’- a simple but powerful feature to circumvent this behaviour. The results were astounding- the number of daily video views on Facebook reached 8 billion in November 2015.

We all have been victims of binge-watching behaviour induced by Netflix’s “Autoplay next episode” feature. Launched to increase user engagement, this feature has delivered great results for Netflix.

Happy Deliveries: Flipkart launched in 2007- and was the first e-commerce player in India to acquire mainstream salience. However, high awareness didn’t translate into proportionate transactions because of several barriers. First, pre-paid deliveries required cards (remember- digital payment system as we know it today was almost non-existent back then) and penetration of cards in India was abysmally low. Second and more importantly, both the category and the brand were quite new, and consumers still didn’t trust the brand to honour its delivery commitments.

That’s when in 2010, Flipkart considered these unique nuances of the Indian market to launch cash on delivery (COD) policy. COD acted as a form of ‘service insurance’ that helped consumers order with confidence, knowing that they had ‘nothing to lose’ in case something went wrong with the delivery. Also, knowing that they could defer the payment encouraged more impulse purchases. This was a big behavioural change that helped the brand overcome trial barriers and gave a big boost to the e-commerce category.

Even today, COD continues to contribute to well over half the e-commerce transactions in India, a number that’s even higher for towns beyond Metros.

Goods once sold can always be returned: across the world, the mattress buying experience was broken for many reasons- it was cumbersome, confusing and costly. And this problem was further amplified in the online scenario, where on top of existing barriers, the absence of touch & feel made consumers think twice before committing.

Casper, launched in 2014 (in the US), was well aware of this challenge. Its revolutionary concept of ‘try before buy’ that gave a no-questions-asked 100-day return policy to its patrons helped to break down several consumer barriers. The reassurance that they had enough time to try and test if the mattress suits them well made consumers much more confident about their purchase.

100-day return was a revolutionary proposition that made Casper a $100 Mn brand within 2 years of its launch. Its success quickly spawned a plethora of me-too competition and today the claim has become a category norm. Closer home, in India too, many new-age D2C brands have started offering 100-day return offer on mattresses. Interestingly, Wakefit has gone ahead and extended this proposition to sofas too, whose purchase is also riddled with barriers similar to mattresses.

Buy Easy, Pay Easy: in the late 2000s India’s consumer durable and gadget industry found itself at an interesting crossroads. Consumers were high on aspiration and desire but the economy was going through a recessionary phase. Though the consumers wanted an aspirational lifestyle, the category faced an ‘Affordability Barrier’.

That’s when manufacturers, retailers and financial institutions came together to devise an ingenious solution- the “Interest-Free EMI”- that went on to become the “sachet” revolution of consumer durables & electronics space, helping brands overcome the obstacle of affordability barrier. Interest-free EMI increased the affordability quotient by reducing upfront cash outlay and splitting the balance into easier payouts, spread over a longer period.

The zero-interest revolution massively increased the penetration of consumer durables in India.

Its category-shaping potential can be gauged from the fact that starting from durables and gadgets, the “No Cost EMI” has extended to sunglasses, jeans, air-ticket, vacations, hair transplants, gym memberships and is today offered by all the leading e-commerce players in India.

An offer you can’t refuse: even as e-commerce was picking up in India, it also had its fair share of sceptics and non-participants, the classic fence-sitters. Flipkart realized that it needed to make them an offer that was “too good to refuse” and hence trigger category trials.

In 2014 Flipkart opened a new chapter in the history of Indian e-commerce by launching the first edition of its Big Billion Sale event. It wasn’t just another e-commerce sales event; it was a true masterclass in how brands could overcome consumer trial barriers.

Launched around the festival season, Flipkart turned it into a “festive celebration” with massive discounts on 70 categories, deals of the hour, lucky draws every hour and unparalleled offers and discounts. Supported by a massive 360-degree marketing and advertising effort, the event was preceded by a huge hype- including full-page newspaper ads and special personalized messages to all registered users a day before the sale. Despite its many flaws (poor delivery experience, crashing of website etc.), the sale was a massive success with three lakh orders received in just 6 hours of time and goods worth $100 million sold in just 10 hours.

Over the years, Flipkart BBD has provided the template for mega-sales events by almost all players in the e-commerce ecosystem including Amazon, Myntra, and Snapdeal. These have been a significant game-changer for e-commerce. The massive marketing campaigns and lucrative discounts offered during this period have helped the category garner a significant share of mind. They have inspired many fence-sitters to confidently make their first transaction, including the value-conscious consumers from Tier 2 and 3 towns. They have also encouraged existing buyers to purchase hitherto untried categories.

In Conclusion

Brand interventions that help to overcome consumer barriers can be both small and big, they could be well marketed or be silent discoveries, and over time they might even become the category hygiene. However, the common theme is that they all attack and overcome specific consumer barriers.

What are some interesting ways you have seen brands hacking their way through consumer barriers?

Write to us at freeflowing@winnerbrands.in. We read all your emails!